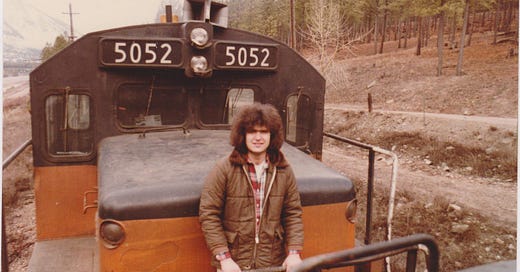

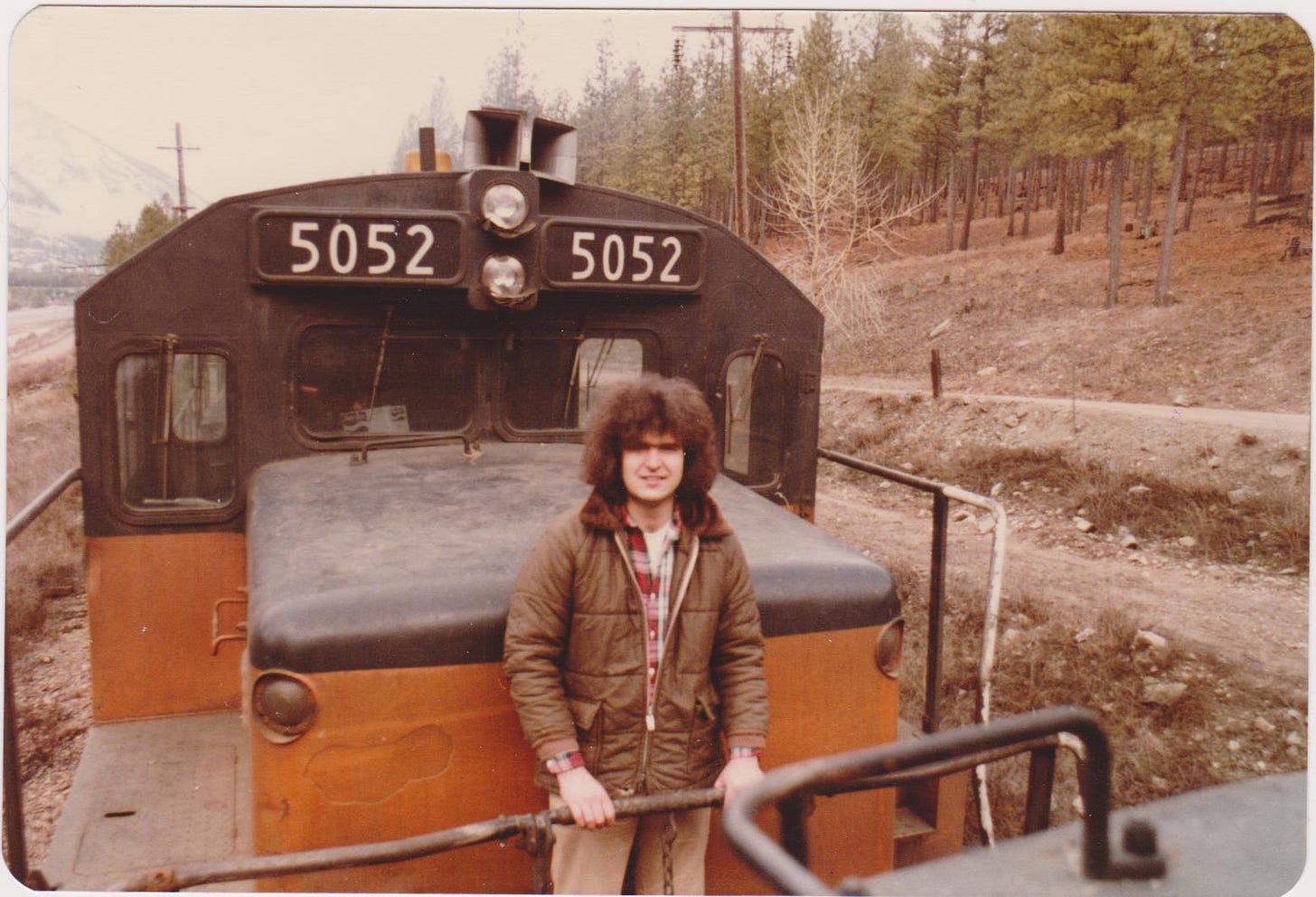

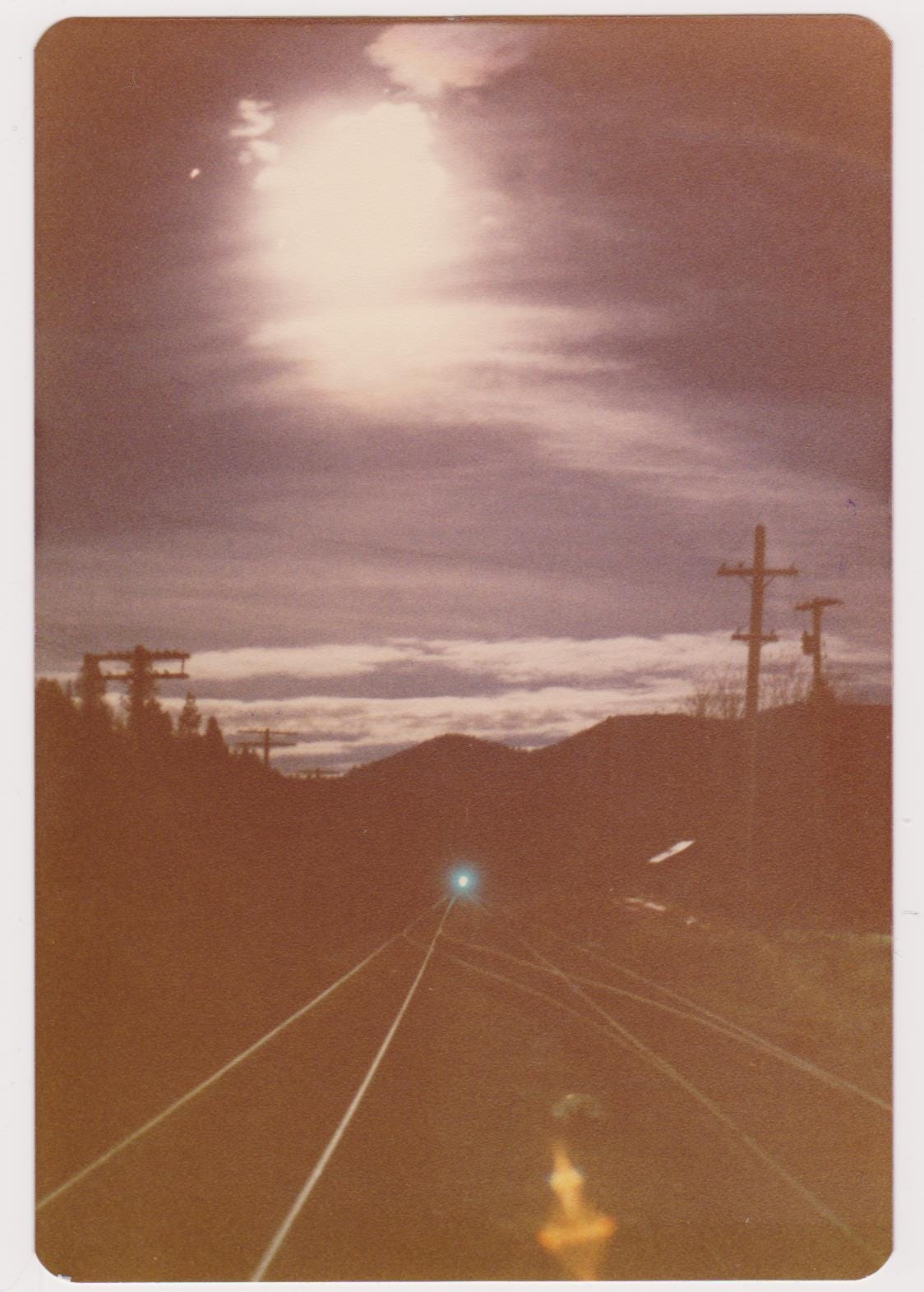

All the Livelong Days The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific had nothin’ and everything to lose that summer in Missoula. Our job – the Catlin Street crossing replacement – four men, water and tools: spike malls and pullers, shovels and picks, rail jacks, tie tongs and wrenches. Shirtless under August sun, we dug and pried at broken ties exposed below the rails, weathered in creosote, sand and cinders. We scanned for tacks to tell us the date a tie was spiked and tamped. Like fingerprints or DNA, those tags were metal proof. Drenched in sweat, we baptized the roadbed – Track pranksters burned black as tunnels. Our hands blistered and bled and cramped. Back on our feet, bent at the knees, we begged for Christ or the lions to be merciful if tongs didn’t bite. Our spines burned till tail bones went numb. Half-done and lightheaded, we broke for a drink. No one ever had to pee. An old gandy dancer shuffled up in suspenders, leaned on his cane. “You boys’re lucky! When I was your age... didn’t have no goddamn machines! That was back in 1929. Those days you earned your pay! Snaked those ties out full length! An’ guys standin’ in line to do it!” Eyes down, we dug for Copenhagen cans and wondered, “Was the old bastard blind?” “You got the wrong railroad,” Billy said, stuck a scoop under the Old Timer’s nose, “they ain’t bought a new shovel since the day you quit! Next year we’re goin’ back to steam!” He squinted and glared, spit in the dirt, stared us down one by one. We went back to cussin’ hardwood and steel, didn’t watch when he limped away. I felt beaten and sore as this wounded railroad, hoardin’ tie tacks cached in my pocket– one, a 1929, would have made that old guy’s day.

Old John was in his eighties when he hired me to dig out a hedge that separated his and the neighbors' yards. John spoke really broken English. His wife spoke no English at all, so there wasn't a lot of talk. He got out a few key words accompanied by gestures and demonstrating for me what he wanted done. I watched him go after those hedge roots with a pick and pulaski the way he must have thrown himself into the railroad roadbed section work he did for forty years for the Milwaukee Road on maintenance crews. I think he hired me to help me out, give me a job, make sure I knew how to handle those tools, do the work, and John’s Mrs. baked treats for me every day I was there. They both smiled a lot, were quite friendly, happy and very private people. A language barrier made it easy to mind their own business and live a quiet life. It made them good neighbors. It only took a few days, but it felt like a trip to Italy. Periodically they would bring out a pitcher of lemonade or a plate of cookies. We smiled a lot. We were both thankful for one another. I barely understood a word they said.

They must have immigrated in the thirties just before the war during the rise of Mussolini. Many of the Milwaukee track laborers in Montana were Italian immigrants. They landed in Avery, Idaho, as Milwaukee roadbed laborers with their daughter. That girl later married one of the Bestwick boys from Alberton, Bud. Or as my dad called him, Herbie. He married Delores after the war, and they had two boys, close to mine and my brother's ages. Bud and my Old Man worked and drank together, did a little hunting and fishing, but mostly it was work and drink, play some cribbage and cards. That's what most of the railroad dads I knew did. Many of those Depression raised WWII vets like Bud and my dad were not easy for their wives, and because they were always on call, waiting to go to work, or working, they didn't make many plans. So if we went anywhere, usually it was with one of our mothers. The mothers made all our school functions, took care of anything a parent had to or was expected to do.

After my mom died, I got note from a friend of mine, one of those railroad kids I grew up with. His memory was that perfect accompaniment to the sympathy card. It seemed to be a poem to me, so like old Willy Carlos Williams, I lined it out and stole it, called it a found poem. “This is just to say” WCW found his own note he converted into a poem. I straight-out stole this baby from Robert Rock.

With Sympathy, Robert a found poem I remember when we were 12 or 13 years old, your mom took us all to Missoula to see a movie. After the movie was over, your mom picked us up, and we was on Higgins Ave “going to a hamburger joint.” Your mom had stopped for a red street light. Some kids in a “hopped-up car” came up beside us and started revving up their engine as if they wanted to race. Your mom started revving up the engine in her car. When the light changed to green the kids bolted away—thinking we was going to race them. All of us kids in your mom’s car started laughing and yelling. We thought it was really fun. This is how I remember your mom— a fun person who was always good to us kids. Your mom and all the other moms in Alberton when we was growing up are in my childhood memories, and I remember something good about all of them. Alberton was a good place to grow up and the moms made it that way. Remember? Because of the railroad our dads was always gone. It was the moms that was always there for us kids.

The moms. I remember going to see Rosemary's Baby at the Wilma theater with Robert and his mom. We were 14 and 15 and there was rape and nudity, not to mention possession and the occult. It avoided an “X” rating but earned its “R” restricted label. Of course, I was impressed with Elsie, Robert's mom in 1968, taking us to this popular horror film. We got in because we were with an adult. I'm not sure if she knew what the movie held, but she never blinked, just kept munching popcorn. Like Robert said, all the moms were cool. They bore the bulk of the parenting in those wild, rapidly changing times.

Danny's mom was fun, too, we learned in more ways than one. We never knew how much fun until the day we were driving around Missoula looking for a “burger joint” before taking in a movie, a whole carload of us, a six pack of sorts. Robert was driving and I was on the passenger side, Danny was in the middle, when we noticed what looked exactly like Danny's folks’ Ford in front of us straight up ahead in our lane stopped for the light. “That looks just like your car, Patch,” I said, and as we rolled closer I noticed the Mineral County plates and chimed again, “Hey, that is your car, isn't it?” I saw his face and knew it was, and it wasn't good. By that time the other guys had tuned in on the two heads in the front seat: a tall man behind the wheel and the silhouette of his mom’s sixties flip hairdoo excitedly bobbing, cozy, right next to the driver who was three times the size of Danny's dad. I felt like shit. Nobody spoke, Danny just looked down. It was one of those moments you never forget. We all felt a heartbreaking embarrassment, shock, a disrespect, a reshuffling of the deck, and imagined how he’d feel returning home that night. I don't remember what we did next, but we all carried the gravity of that situation away with us. We felt his pain, shame, sadness, loss of faith, and a kind of betrayal.

Danny died at forty of a heart attack. I always felt bad that I was the big-mouth who zeroed in on it: a lifelong susceptibility to foot-in-mouth disease. Years later I moved in on his girlfriend in high school after she'd broken up with him, and I knew that broke his heart, too. He felt betrayed by me for a few years, but we managed to put all that behind us after a few years when he found the love of his life and got married. Maybe it took that long because I married that girl who dumped him, the one he naively thought he would marry at sixteen. It was a different, simpler time. I married her at eighteen. I'm glad we reclaimed our friendship. He was a really fun and funny guy who’d laugh till he cried. An Italian, whose grandparents also came from Italy to work on the railroad. He loved Mario Lanza, Rocky Marciano, Dean Martin, everything Italian. He loved Three Dog Night, The Guess Who, and Sophia Loren. And he was short and passionate like his dad, a bit of a little guy complex. He was a force. It was in his DNA, that passion he exuded in every way. He was tough and as determined as he was genuine and gentle, but above everything else, he was hilarious. Isn't that the way it is? If you're carrying pain inside, the best way to handle more shit is with humor: laughter, make others laugh, so you can laugh, too.

The Owl Is Back Again

Sorry I missed your wedding reception,

got lost along the way (should’ve ignored

Casteneda’s directions).

When I finally arrived and settled

on grass outside the bar, down

by the lake shore, I watched an owl prey

on a gopher in daylight,

thought it rather strange. It didn’t

leave but perched on a pole to eat its kill,

silent as bells on the masts of sailboats

tethered in the bay below.

Morning, twenty years ago,

we woke before dawn after running the town

all night, our sleeping bags damp with dew.

Dawn shadows faded on the mountain

across the river as new light filled

the valley up, and rocky cliffs glowed

vibrant gold. When I looked at you,

you blinked, slowly turned your head,

puffy-eyed, hair matted into tufts.

The owl’s come again to tempt the sun,

hungry for dusk and nocturnal blood.

It waits for us to lose ourselves

in our business on the ground,

then spreads its wings, talons ready,

falls easy as autumn leaves.

How does the owl decide who

to choose and when? Did it take you

away to speak the wind?This is an excerpt from a long hybrid memoir thing, “podunk no horse,” prose and poems, which I thought I’d share parts of here. Thanks to Judith Annie McDonnell for the pen and ink of the owl and the inside of an old Milwaukee locomotive.

A gandy dancing Owl without RR tie bruised knuckles prefers to eat in daylight. Wise owls never sign on for that kind of work.

Your gandy dancing experience rings true!