Letter to Hugo from a Ghost

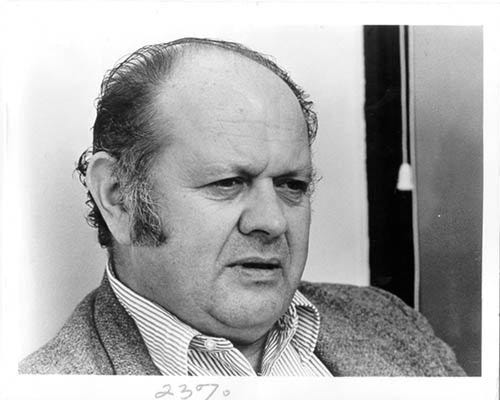

Dear Dick: I can't believe it's been over forty years since you went west. So I don't know why you visited me last night. Maybe it had something to do with your letters & dreams book. That's the beauty of dreams, you can find threads in them, but there's no way to completely understand them—like poems. You reminded me of my Old Man, both of you WWII vets, loners who spent a lot of time in your heads and tried to drink your way out of it. Now I'm years older than you were when you died, yet I'm still looking for your approval thanks to my dad. I guess it was the melancholy and the mystery of your alcohol escape that drew me to your poems; along with your eye and ear for the world; your need to move, drive those landscapes, and find rundown towns on the verge of collapse that reflected your broken heart. You found yourself wherever you went. Isn't that the way of it always? The hope is that somewhere, somehow, someday you'll heal. I think I have for the most part, but the ghost inside me remains. It doesn't go away. Did it ever leave you alone? I still see it there in your later poems. As kids I think we both lived lifetimes in our heads, managed to escape our own little Hells by—whistling in the dark—talking to ourselves. I remember hearing you say in that “Loose Gravel” film you were looking at the sky one day when you were a kid, and it just hit you that you were in love with your own observations of things, and you realized it was something you'd do for the rest of your life. The same thing happened to me lying on my back watching the world go by: the clouds moving across the sky, birds, the wind in the trees, the sounds around me and how it felt cool on the ground and smelled or earth and grass. It was such a soothing distraction from the unhappy realities of my day, and the days I knew would follow. That's why I was drawn to you. I recognized the ghost in you, so it was great to see you last night sitting at the bar, most likely Harold's but also Chet's and Charlie's and the Speakeasy: stools and beer and dark. No sunny fishing dream, but there were interruptions of light each time the door opened and lit your face, the room. You were happy, smiling and laughing at the story I told about that time I took you my stack of poems and how I asked you to take a peek at them and tell me what you thought. It was just months before you died. I remember my disappointment when you told me I should try my hand at fiction because what you read “just wasn't poetry.” You laughed heartily and took a swig of beer. There was no cigarette smoke though we both were Camel men back then. I don't remember how the dream ended. Maybe you went fishing or wrote a poem or was distracted by something else. Maybe I just gave up on you. I wish I would have thanked you sincerely for your advice. It helped my resolve. Being bull-headed I kept at it, began writing “unpoems,” determined to prove you wrong, the way you dove into “epistolary poems” pooh-poohed by the critics. But I'm sorry to say you died on me, on all of us, too young. So here you go, a letter from a ghost to the grave. Drop in anytime you're feeling thirsty or want to go fishing. I can bait fish in a dream, but prefer the creeks and a fly rod. Cheers, Dick! Till our next rendezvous. Before you know it, I'll be haunting dreamland with you. A former student and still a fan, Mark.Those of us coming of age in the sixties and seventies were wowed by the personality and poetry of Richard Hugo (1923-1982). We recognized him, felt we knew him. He wrote about regular western activities and people. He wrote about where he came from and where he was at. And he lived his life openly and wrote about it. That was unusual from my experiences of reading poets. He smoked, drank too much, was insecure and often inappropriate with women. He was honest to a fault. And he was a professor at the University of Montana. He wrote about failed love affairs, drinking, and fishing in a musical, free verse style distinctly his own.

My old friend, Ed Lahey, who studied and drank with Hugo, told me a story: that one time Dick was asked by the chairman of the English department to read to him and the graduate writers from the manuscript for Hugo’s new book of poems. Flattered, Dick obliged, but after his reading, the department chair offered to give Dick some notes on revisions for some of the poems Hugo had read. Ed said Hugo stared at the man, then slammed his fist on the table making the coffee cups jump, and said, “If you don’t like my poems, you don’t like me!” Then he stormed out of the room. Class dismissed.

The book that “laid me in the shade” was The Lady in Kicking Horse Reservoir. Hugo traveled the state and stopped in the small towns. What he found were poems. His imagination found Richard Hugo there. I knew many of these places and it made me rethink what poetry was, what a poet was. The local was being elevated to art, and a whole lot of locals (regular working class folk like me) were finding the poet in themselves, and I secretly thought maybe I could be a poet.

In the mid-seventies I signed up for his undergrad poetry class. I was very insecure about it. What was a poet? How did you know if you were or could be a poet? So I went to his class and was bowled over by the workshop process and Hugo’s frank, and animated if not abrasive style of responding to poems, a mixture of delivering a deadly serious and personal take often laced with sarcastic humor and always tempered with a bit of self deprecation. It terrified me. So I withdrew from school and went to work. The certainty that I often encountered in academic classes unsettled me. I wasn’t certain about much, but I was certain that I didn’t like anyone who was too certain about anything. I figured I’d just keep reading and writing on my own, entertain my private fantasy of being a poet.

And if imitation is the highest form of flattery, Hugo must have been embarrassed with all the flatterers. So many of his students wrote poems that echoed Dick’s style that it became a bit of a joke. Many people thought that showed him to be a lesser teacher because of it. I don’t think you can blame that (if you like blaming) on Hugo. He was a strong and charming personality. His students loved him in spite of his personal flaws. He was generous. Teachers help writers with craft and introduce them to other poets, but in the end we each have to find our own path and trust ourselves, ignore what the “tellers” have to say.

Here’s a taste of Dick! The intro to Annick Smith’s film Kicking the Loose Gravel Home.

So, thank you, Dick! Now let me have some parody fun with your voice, and I hope this flattery has you rolling with laughter in your grave. Cheers!

THE FISHING KING for Dick Hugo You drove here to catch a Superior fish, got snagged in The Montana Bar. This bartender knows your word is good for nothing, runs you a tab all cutthroat feel is wrong as shadow ghosts on a stream and cracked as your life—an honest need to lie about sizes of fish you've caught and women you've never had. Maybe you'll write her a poem some day you tell the skirt two stools away who noses your artsy Royal Wolf—cast like a spell on a beaver pond, always dim as your opinion or the mirror at closing time. When you order two Turkeys and beer backs, she asks where you plan on dipping your worm. You curse her ancestors, her children and dog, tell her you're proud of your rhythm and fly, don't cotton to vulgar slugs or slime that sully the graves of true fishermen and swear you'll piss on the bejesus bar if she keeps talking trash or bait. The brazen twitch steals your keys when the bartender points to the door. The air outside, stifling when you came opens lilac in her hair. She suggests you try her night crawler with a little taste of corn and drives you fast to the mouth of Trout Creek, points out her favorite hole. You cast, retrieve, cast, retrieve, cast, then let it go. Your fly rides the current slow, before a Rainbow flashes and dances—tail fin arcing the sky. The hook is set. You play it long, till it rolls its heaving side. She opens her Busch in cottonwood shade and sucks a Lucky Strike. Her wink tells more than crippled words— you know your rod and line. You finish the beer and afternoon, drive her back to the Four Aces Saloon where a run of jacks could drown. You head for Chet's in Alberton on the frontage road you know for sure will never lead you home. When your tongue wakes gray at Forest Grove, the moon is full and blue as your Buick flirting with suicide, halfway down the boat ramp, its grill in soothing tide. Your head throbs like a knife wound as you search for the roll of twenties gone and know you'll never find. You think her name was Brooke. No. Wasn't it Dolly Brown? A damn good catch for a fat clown who calls all water pain. You remember her skin, those golden spots— pretty as they come, and admit your pole could never again stand up to her spinning dare. Your silly grimace begs a smile you want to wear back to town. Forget this river, your pride and youth you sold for cheap disdain. You know reverse like hangovers will take you back to war. Inside you're still the shriveled worm good booze won't let you ignore. She left you dry as rotting carp pitched high into the weeds—rank air you crave like your broken need to snare this poem or that Superior girl who claimed you both a Missoula sucker and The Clark Fork Fishing King.

Here are a handful of poems from The Imitation Blues, 2017, FootHills Publishing.