Great Bear Memories, Forever

—for Jarrett Potter (1953-1980)

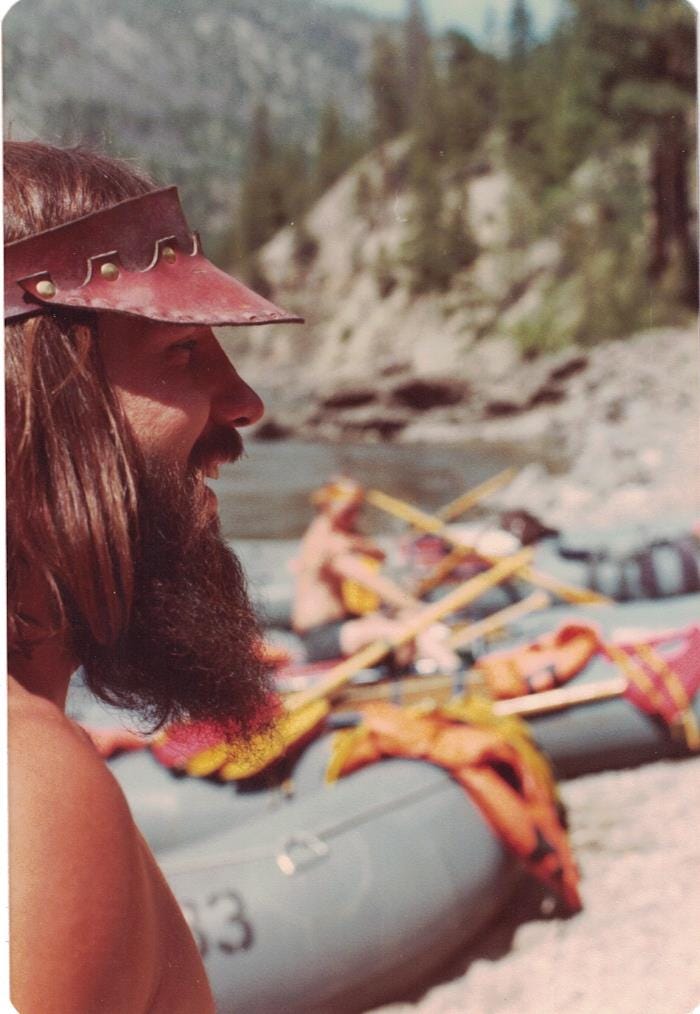

He is an Indian,

a mountain man,

sporting long hair and a beard,

the earth is his temple.

He has broad shoulders

and a long thin body

that narrows to the waist.

His hips, legs, arms and hands

are big and strong

like Popeye's.

He moves like a bear

up and down hills

and football fields,

Rolling Thunder.

He is that ideal blend

of man and woman,

as strong as a mule

and as gentle as a kitten.

He is a lover

of all things.

A romantic warrior

defending the weak

and respecting the strong.

He is a hunter

not a killer,

always at home on a snow covered ridge at dawn

or riding a swelling river in searching spring runoff,

high, aware, intense and close,

even now that he's returned

to the mystical womb of mother earth,

he is near.

He is common sense,

practical as a Montana winter,

methodical as an old outfitter.

He rages, he fights

for truth and justice.

He absorbs, he accepts

what he can't affect.

He reaches out and touches everyone,

unlocking their secrets

that swim naked

in the warm pools of light

that are the open eyes of understanding,

his mother's eyes.

Where he first found

genuine, committed love,

adrift in the sea of faces

called life.

The blank stares

of a petty societal bent

are slapped around

and pushed into

the Now and Love

that is Jerry Potter,

The Pathfinder.

He is a force,

a spirit

so good

that he was saved the pain

of the coming years.

A minority.

He has walked in many other pairs of moccasins

and judged not.

A survivor.

Money isn't important to Jerry.

It comes, it goes.

Greed

he doesn't understand.

He's the Wizard

in his mountain home

with a song for every man.

Music makes him sing

and his music inside

radiates in everyone

who stops to listen.

And now he's free,

unencumbered by physical form,

to fly with the eagles,

to wrestle with the bears

and to know the true beauty

that all men and women

fall short of

in their fear

of living and dying

together,

alone.

The generous teacher,

a soft tutor in live,

has filled his classroom

in death.

The hungry student,

the great curious lover,

has passed the test

with honors.

Not a perfect score

but he never cheated.

An honest man,

one of the best.

That's why it's so hard

to see him go.

I miss him so.

He is unique

in a “my society.”

An unselfish man,

a giver,

a helper,

an eternal brother

and great bear lover.

He is talented freedom

oaring through my veins

in cut-offs and sneakers,

nose in the wind

and twinkling eyes, smiling,

a Marlboro pinched between his lips,

chuckling

a deep husky laugh

as he bows into a wave,

feeling the force of a million waterbabies

grab and hold him,

whispering life's secrets,

then spitting him up and out

into the sunshine

screaming

for one more,

one more wave,

one more football game,

one more hunting trip,

one more woman to love

and time,

one more euphoric moment

before the game is over.

Your time was good time, Jerry,

and we know you haven't gone,

for your monkey wrench glistens on moonlit nights

reflecting what's important

to romantic warriors,

to newborn babies and to grandmother earth,

besides, it's easier now,

knowing that death

is just a bear hug away.

That was written in November of 1980, and this is my account of the first significant death of a friend my age. Years before Kurt Cobain's death triggered the 27 Club, my generation had noted the coincidental deaths of so many of our rock-n-roll heroes at age 27: Brian Jones, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix. Those high-profile early exits had prompted a high school teacher of ours to cynically (and sadly) joke: “Live fast, die young, and have a beautiful corpse!” It was his attempt to warn us of the dangers of that reckless invincibility attitude of youth once they'd left home and struck out on their own.

Back in the late sixties and early seventies it seemed like young people were dying in droves every day, if not in Vietnam or on American streets, from some Romeo & Juliet bloody over-reaction usually involving booze and cars or an overdose of drugs. Dylan told us not to trust anyone over 30. Most of us couldn't envision living to see 40. Death seemed inevitable, it was everywhere. Living for the moment became our way of life. Getting fucked-up became a daily normal we called “checking out” or “having fun” . . . for tomorrow we could be dead. Patterns, habits, we are creatures of habit, psychological addicts. All our highs and lows were intensified, celebrated or mourned, with an increased use of a variety of intoxicants.

Wasted days, wasted nights, wasted dollars, wasted life. I describe my twenties as a blast and a blur, so the whole voodoo conspiracy of the 27 Club, the mysterious deaths of musicians at the age of 27, is not hard to understand. Living fast and furious, as our old teacher pointed out, increases the odds one won't see 30 or have to worry about trusting themselves. So many of us took those chances, made that trip. We all suffered survivors’ guilt when we had to bury our friends. That individual for me was Jerry Potter.

He was a fifth grader when his family moved in. They bought a strip of land at Cyr just west of Alberton between the railroad tracks and the river. They came from Arlee on the Flathead Reservation, the first Indian family we had in school. We were a bunch of isolated, insulated white kids, naïve to the ways of the broader world. I don't remember even registering it that Jerry was an Indian kid. He was just another boy but not just any boy. He was quiet, pleasant, strong and fast, but what stood out for me was his kindness. He was open and easy going. Often new kids tried to prove themselves. Jerry didn't seem to be afraid. He got along with everyone.

Alberton was a small railroad town, working class, nobody was rich, but some had less than the average. Jerry's family had less of the things we took for granted like two or three changes of clothes. His school clothes amounted to a new shirt and pair of pants. Each fall at recess we boys played touch football in the school yard, and everybody wanted Jerry on their team because of his strength and speed. I remember the day he opted out of playing because he was wearing his new shirt. He said his dad would kill him if he got dirty or ruined the new shirt. Chadwick swore no one would touch Jerry's shirt, begged him to play, and threatened to beat up anyone who touched Potter's shirt. So Jerry agreed to play. As players were picked for both teams, Chadwick and Potter wound up on opposite sides. Toward the end of the recess, Potter got the ball and broke through the line blowing by everyone and streaking toward the goal. The only one who had a shot at touching him was Chadwick who tried to grab him and got the tail of his shirt, tearing it and stripping off the buttons. Potter whirled, stopped, looked down at his shirt, stunned, then let out a wail promising Chadwick's death and took off after him. Chadwick was running before Potter took off. There were no teachers monitoring the touch football game, but the problem soon came to their attention as we all watched Potter screaming and chasing Chadwick around the school yard a couple of times, gaining on him each lap. Chadwick was terrified, ran for his life, was losing ground when finally the teachers got out there and intercepted them. Potter was hysterical. Chadwick apologized profusely and promised to buy a new shirt. After school that day, Potter went home with Chadwick to make arrangements for the new shirt and stayed for dinner. Jerry never wasted much time holding a grudge. By the end of the day he was his same old pleasant self. We learned the Potter's Field Rule that day, it was the Golden Rule: be good to me and I'll be good to you. Loyalty is what made him a great team player, he never placed himself above others or the team, and he demanded the same behavior from his teammates.

Jerry was a year ahead of me in school, but he never played the seniority card or acted like he was better or more privileged than others. It was just his nature, who he was, like his older brother, and upon meeting their mother, it was apparent why. She was undoubtedly one of the kindest, sweetest people I have ever known, and while all of us have traits from both parents, those Potter boys got a big dose of Mom.

After graduating in '72, I moved to Missoula, got married in '73 and lived there until '77, so I saw less of Potter in those years though we still mixed in the same group which involved rafting, partying, and hanging out in the bars. By '77 the air quality in Missoula was getting the best of Pam who developed asthma, so we decided to move back to Alberton, head upwind to find some fresh air. It was a chance to spend more time with Potter. He was working for Western Waters as a rafting guide in the summers. The rest of the year he helped his dad who ran a few head of cattle. We moved some houses for his dad. That was fun learning from Potter how to jack up a house and move it away. We cut firewood and sold it, did a lot of hunting in the fall, kept our ears open for ways to make a few bucks. And there was always our commitment to the team, each other, our friends. That social glue had always involved alcohol, but by this time included psychedelics, speed, coke, a variety of pills, ups and downs, but neither of us were interested in needles. Those wild years from'77 to '80 we described as fun, ignoring the blackouts and brushes with death. Our mantra back then all boomers will recall could be summed up in that classic Commander Cody line: there's a whole lotta things that I ain't done, but I ain't never had too much fun!

There were times when I knew he'd been out of work and not eating regularly or much at all, so I'd invite him to dinner. We ate a lot of beans, stews, potatoes and eggs, and there was always room for one or two more at the table. He was the most polite dinner guest ever, very slowly dishing up, buttering his cornbread, salting and peppering his bowl, adding a few drops of Tabasco. Then he would savor each bite, chewing slowly and talking in that relaxed drawl the whole time. I would be wolfing down a bowl and dishing another, slopping crumbs and dribbling honey on my fingers and another piece of cornbread, and by the time I'd stuffed myself and pushed back from the table, he might be halfway through that first bowl, complimenting the cook and asking questions about the recipe. It just hit me: Potter was a gentleman or the Indian equivalent of that well-mannered, courteous behavior. He may not have eaten a full meal in three days, but he took a good half hour to appreciate and consume (only one!) serving of food.

So the fact that it was Potter that met his demise at 27, made no sense to us. Out of all of us, he was the thoughtful, carefully meticulous one, an old man in a young body. Actually I did have a foreshadowing of it right before he died. In the summer of 1980, Pam and I had moved to Bozeman in hopes of me getting a student loan and going to film school. The Milwaukee Road had gone bankrupt and shut down in the spring. Many were leaving. The town I'd grown up in had lost its identity. Everything seemed to be up in the air. And while Jerry had been flying high after falling in love with a woman for the first time in a long time, by July he found himself nursing a broken heart. So he moved down to St. Regis to tend to a property for his dad. He was not himself, and alcohol wasn't helping his depression. Bozeman turned out to be a bust for us, too. No banks were loaning money, so I spent my days checking on spot labor jobs, writing in coffee shops, and drinking whiskey in the afternoons. I found a few jobs moving furniture and cleaning up construction sites. Pam had a job at a grocery store she hated almost as much as finding me drunk and depressed when she got off work. So when we got the invite to return to Alberton for a Halloween party, we were excited about going home and visiting our friends and families.

Before we headed to the party, we stopped into the Sportsman's to see if anyone was there, and I saw Jerry sitting alone at the end of the bar, a glass of “Ta-kill-ya” in front of him. I snuck up on him in an attempt at a playful scare. When he turned to look at who it was, his dark face almost smiled, but it didn't quite happen. There was a brief flash in his eyes, but he was deep in an unhappy place. His stone expression was an intoxicated blend of sadness and anger—depression. We talked briefly. I did most of the talking. He told me he'd just stopped in on a whim, that he was headed back to the west end where he was spending most of his time. When I first walked into the bar, I noticed his ex-girlfriend sitting on her new boyfriend's lap. I invited him to come to the party with us, but he said he was ready to hit the road. It was sad and a little scary because I'd never seen him like that. And that turned out to be the last time I saw him alive. In hindsight, I amended that statement to: no, I think his spirit had already left.

We took some acid at that party, and when that started to kick in, it worked the way acid works to unlock us, open us, expose the who of where we are. I found myself falling into this bottomless pit of darkness, so I went out the back door of the house that was a mere fifty feet from the old Milwaukee main line. I stood on the tracks in the silence, under a full moon, the green signal still shining east of town, letting us know the track was clear, unaware that the trains were gone. I couldn't shake the foreboding or the overwhelming emotional bum trip that I assumed probably had a lot to do with the end of the railroad, a way of life, maybe the end of the town, and certainly the end of our old life there since we'd already left, a homesickness without a home to go to.

So we returned to Bozeman even more depressed than when we'd left there seeking to lighten our perspective. And since I wasn't in Alberton for the fall hunting season, I was truly missing those trips into the mountains with Potter and couldn’t stop thinking about the last time I saw him. A week later I awoke to the phone ringing on a Sunday morning way too early. That's never a good news call, particularly after a late night of drinking with another old friend I’d grown up with. Charlie, another lifelong friend of mine said, “Hey . . . have you heard? . . . Jerry died in a car wreck at two o'clock this morning.” I was shocked but not surprised. Hungover, the first thing that came to my foggy mind was that Jerry was a tequila drinker which I rarely touched, but had consumed a few pitchers of the night before. It seemed the universe was always sending these coded messages. Unfortunately there was nothing coded about this news. He was driving back to St. Regis after closing the bar in Superior. So we headed back over for the funeral. I remember he looked beautiful in his coffin, but not as beautiful as he was in life. He was 27, that crazy age again. You'd think all that would have sobered us up, but things rarely are that simple. We replaced our old mantra for fun with a new one: “Only the good die young.”

Pissed at Potter’s Funeral

*

That frosty November day,

Tom stood at the edge of the grave

we'd dug the night before.

The preacher, stern, Bible in hand,

prayed God have mercy on Potter's soul.

Guilty as Potter of too much fun, the rest of us

bowed our heads, bit our tongues,

but Tom never played by the rules.

*

He whistled, barked out a staccato laugh,

then poured Budweiser on the casket.

His cackle yanked and lashed

every sorry neck erect.

B.W. and Rastus both sprung for him,

grabbed his arms and shook him hard,

hissed he'd better knock it off

or they were going to kick his ass,

but Tom was drunk, beyond, and crazy-strong.

He threatened to piss in the grave.

*

Only Potter could handle him well,

speaking those low, gentle tones

he'd used to calm horses and dogs.

I watched the pine box in the bottom

of the hole, knew easy was over

for good. Tom struggled to open his zipper.

The three of them almost went down.

Potter's mother let go of the minister's

arm, crossed to Tom and sheltered

his hands with her hands.

*

She smiled. Her thumbs rubbed

the ridges of his knuckles,

and he melted, bent forward and cried.

She whispered in his ear, slipped her arm

through his arm. The two of them

shuffled away. The wind swayed tall pines

that banked the plot. I looked west,

and two ravens hovered motionless

in currents above the river, then peeled off

and disappeared downstream. There was snow

up Whiskey Gulch. I didn't know what to do,

*

so I scooped the first shovel of dirt in the grave.

It covered the inlaid cross on the coffin lid

and interred the gifts Tom left

for Potter's journey: a pipe

and beaded medicine pouch—

beside the empty beer can.

I see him in my minds eye as he was when he left us. Never aging, forever 27. The weekend following his death he was supposed to have made his way to Great Falls to drive back to Missoula with me because he didn't want me to drive over the pass in a VW bug with a newborn, a 6 year old & a dog- by myself. I miss him every day.

A very touching, heartfelt tribute to your friend.